The stable light air machine and the only foamie worth considering is Dreamflight's Alula.

In a total affront to common sense, I find myself surrounded by Ordnance Survey maps and surfing Google Earth in the initial planning stages of my next road trip. The missus and kids will soon be escorting granny to sunnier climes once again, and with no real hankering to act as taxi driver between cluttered rural markets and designer shopping outlets I’ve played the stack of brownie points accumulated over the winter to enable me to enjoy two weeks of unabated bachelordom in the company of a car stuffed full of gliders.

Whilst pondering which beautiful UK slopes to frequent this time around, I realise that there are a few gaping holes in the quiver of acquaintances that will be sharing this trip with me. With an aspiration to cover every slope condition I encounter when out on the road, those holes need plugging up; if I’ve said it once, I’ve said it a thousand times – it’s all about having the right toy for the job. Heading to the slope with the best models for the particular hill and the expected conditions for the day ahead is the easiest way to get your flying day off to a great start. This means you must know the nuances of your individual models really well, and to a certain extent also be able to predict the conditions at the slope and read the message behind the available weather reports.

The lightweight Ruby has been quite the surprise and a versatile performer in lighter winds.

GLIDER CACHE

Flying trips like this are made somewhat easier by building up a collection of models to form a ‘slope arsenal’ that underpins the sort of flying you really like to do. An effective slope arsenal will have a model that will perform well for every flying condition, from the lightest inland waft to the strongest coastal gale. Each ‘plane will have a range of conditions that it can cover based on its design, construction and ballastability. There’ll ideally be a little overlap between models in case you decommission one, and if you’re really serious about getting in the maximum flying time you should make sure that you have a reserve. Having a crack in your arsenal could have you either spectating or running the possibility of getting in everyone’s way as you fly a model not suited to the conditions.

There are many facets to slope soaring, and I can derive just as much pleasure from flying my Alula around a motorway services lorry park as I can my Jart in huge coastal air off a 1000ft cliff. In this respect, then, there are many ways to categorise models within a slope arsenal: suitability for a venue, a particular style of flight, material of construction, even models of a suitable genre! I prefer to think about the weather forecasts, the venue, the landing zone, other expected slope users and recovery of the model from down the front if need be. But all of these parameters are less important to me than the initial one I use to select aircraft for a particular day – wind speed.

Wind speed can, of course, create different conditions on different slopes. 5 mph up the front of your average sand dune isn’t the same as 5 mph up the front of a 1000ft bowl like the Bwlch. A little generalisation is in order, then. With some luck, a look at some of my personal slope arsenal I use in different wind speed conditions might give you some ideas for your own.

The Limit EX (RCM&E plan) – it's hard to find a slope where nobody has flown one of these fun machines.

0 – 5 MPH

These conditions will generally see slope pilots sitting on their backsides telling anecdotes. However, there are models that fill this category nicely, and if we stay away from electric power and consider slope lift only, the favourite has to be the Dreamflight Alula. Notwithstanding the enormous success that this model has been, I’m tempted to move away from foamies these days and have managed to get my hands on Nemo, a tiny little Mosquito class discus launch glider. At just 75cm span and weighing in at 95g this little moulded carbon fibre and glass featherweight can be side arm launched 2 – 3 times as high as an Alula for the same effort, and tracks upwards as straight as a die. With a glide as flat as a slate layers nail bag and an ability to circle in around 4ft or so, the Nemo has rekindled an interest in this class of model that was thwarted by my slope soaring accident and severely dislocated ankle some years ago.

5 – 10 MPH

Most self-respecting slopes will work perfectly well at these wind speeds, and the door is open for most of the lighter-loaded models in the arsenal. Aircraft that are simply divine to play with in these sorts of winds would be fun soarers like the Multiplex Easy Glider, my Vladimir’s Models Organic, which is a 2.5m span lightweight thermal machine with a moulded D-box ahead of a built-up wing (at the more expensive end of the quiver), and my recently tried and tested Ruby, available from South Coast Sailplanes. The very low wing loadings of these models mean a 10mph breeze up even a crappy hill will get them away easily. And let’s not forget the Air One Mini which, while it will also cope with much stiffer conditions, is a real pleasure to scratch around in these wisps of lift.

10 – 20 MPH

We’re moving into the normal sort of conditions now, and my big moulded race machines will be getting rigged. Current cream of the crop is my Teutonic twosome of Caldera and Freestyler, an investment representing towards £2500 spread across two models! At the bottom end of this wind speed band, my British-made Falcon and VV Models New Sting rule the roost and really do outperform many other models in light conditions.

Moving into the middle of this wind speed band my Compact Wizard and Acacia 2 might see some airtime, and if it’s a question of wingspan I have the Slopeblasters Luna and PCM models Erwin DS, both spanning 2m. Similarly, my (now rare) Joe Cormier Mach One wingeron might see some air but it can be a struggle to rig on the hillside. There’s also my diminutive Cravallo (the famous eBay plank) and perhaps, for that retro feel, the Chris Foss Middle Phase. On the foamie front any decent combat wing, like the McMeekin Predator or my lad’s Irvine X-IT, will be having a good time. Mind you, we’re also getting into the realm of the heavy 60” EPP pylon model, where for my money the NCFM Halfpipe still takes some beating. Just for kicks models like the Birdworks Zipper (now available from www.offtheedge.com.au) or the RCM&E free plan Limit EX (though mine is an original Limit) can be really great. A gap exists here for another model (a foamie for those tight, dodgy LZ sites or EP crowded skies) and in this respect a Richter Weasel Pro is currently on the bench in preparation for the trip. This wind speed band is also just perfect for some nice scale soaring, and whilst this isn’t really my bag there’s a certain element of pride in presenting a scale model properly. Mmm – I must get my Multiplex DG600 Evo finished.

Chris Foss' evergreen Middle Phase.

20 – 30 MPH

Now we’re talking. This is getting to be a good day at most slopes, though many pilots I’ve come across on these trips do consider such wind speeds to be a little high for their liking. The moulded racers will really be knocking on, whilst the lighter lead sleds can also come out to play. Lucky owners of a Higgins R3 Rodent will find it nice in these winds without ballast, but my R1 will still be sat in the car next to my heavy Jart. Mind you, my ever-so-secret and rarest of the rare Feldvebel Kestrel will be out if the skies are quiet. This model really does have to be flown to be believed; it doesn’t look much, but once it gets on step it’s a huge big sky carver. Dave Reese (Lift Ticket) described the Kestrel as the best sport plane he’s ever flown, and I know just where he’s coming from. The Kestrel is a full pitcheron, and compliments my Mach One very nicely in these kind of conditions.

Winds in this band can provide some really awesome lift without turbulence on most hills; aerobatics become ever easier and energy retention can be kept in, to the envy of many-a power flier. Aerobats like the Lanyu Slope Trick and new arrival the Wasabi (www.flybiwo.com) were really made for days like these.

30 – 45 MPH

Winds of this speed will be getting to the point where some models become difficult to launch without assistance. Any compression on the lip of the hill can create a little turbulence, and holding a sizeable model like a 3m racer aloft with one hand can cause no end of launching problems. Smaller-span stuff does make it easier, and on most slopes you’ll begin to see high-end models being replaced in the air by heavier EPP aircraft. Some hills will be starting to get a little blown out, and ballastability comes into play now as the performance of ‘lighter wind’ machines is altered to help them resist potential blow-back from runs along the edge.

I might now be contemplating a play with my Opus VDS, which is essentially my set-aside DS model, although she does like an outing on the front side now and again.

The superlative Jart.

45 – 65 MPH

The lift can be getting epic now, and my 74oz Jart just loves this sort of blow, especially on a big hill like the Great Orme in North Wales. She’s very easy to launch single-handed and carves the sky in these wind conditions with no fuss at all. My other lead sleds like the Doug Reel Barracuda, Higgins F-20 and the Shredda (Fermin Death Missile) will out fly any lighter machines; a little care needs to be given to the landings, which tend to be single point, javelin-like approaches rather than nice, floaty alightments.

65 – 100 MPH

Yes, there really are models easily capable of flying in 100mph winds! This is Higgins Rodent territory, and for these conditions there really is nothing I know to touch it. I’m lucky enough to own an original clipped wing R1 version, which has a higher loading, shorter span, different empennage and narrower (sharper) fuselage than the current R3. I’ve regularly flown the R1 in winds at the lower end of this band, and on one epic, unforgettable occasion, in winds topping 100mph.

If you do venture out in these sort of winds don’t expect to be landing anything gracefully, especially at the top end of the bracket. Getting these heavily loaded models down is more a case of trying to crash slowly – my model still bears the scars, dents and chipped paint often associated with typical Higgins Rodent flight. My transmitter aerial gets replaced by a base-loaded whip antennae and I definitely need someone to launch the model for me as just getting to the edge can be a particular source of amusement on a really ‘big’ day. Expect your eyes to be watering profusely unless you’re wearing goggles, and any models prone to control surface flutter at high speed will probably all have crashed by now! I’m fairly sure the Jart will play out in these kind of winds, having test-flown it initially at the lower end of this band, but why would I want to risk her when there’s a Rodent in the collection that will suck up these winds with relative ease?

No, there’s only one toy I’ve found that really rocks in this sort of blow, and if you get a chance to own one you should take it. The Higgins Rodent is the perfect complement to any sloper’s arsenal.

- This article was first published in 2008.

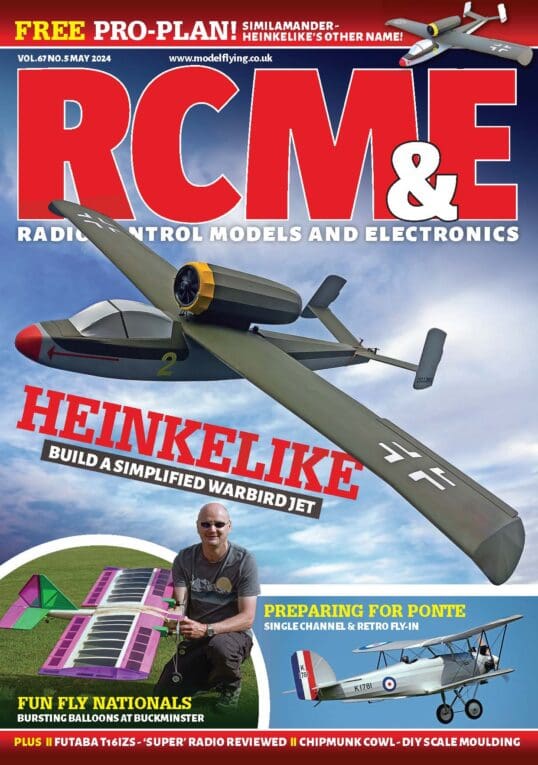

- Read Andy's On The Edge Column in RCM&E.